Awaiting the Inevitable Return of Emotet

Summary

Emotet is probably the most prolific of the recent malware distribution operations. They often change their malware to ensure it is not detected by any anti-virus software. Even though the Emotet botnet is on “spam break” recent changes in a component of the malware has prompted Hornetsecurity’s Security Lab to take a look at the latest version of Emotet in order to be prepared for its next steps. Emotet has added new code obfuscation techniques. But the Security Lab explains how it can still be analyzed.

The updates to Emotet’s loader do not impact Hornetsecurity’s filters as the Emotet loader is never send directly attached to an email. However, the presented analysis and downloadable Ghidra scripts can help other researchers to jump start their Emotet reverse engineering despite the added obfuscation.

Background

The malware now commonly known as Emotet was first observed in 2014. It was a banking trojan stealing banking details and banking login credentials from victims. But it pivoted to a malware-as-a-service (MaaS) operation providing malware distribution services to other cybercriminals.

Emotet Infection Chain

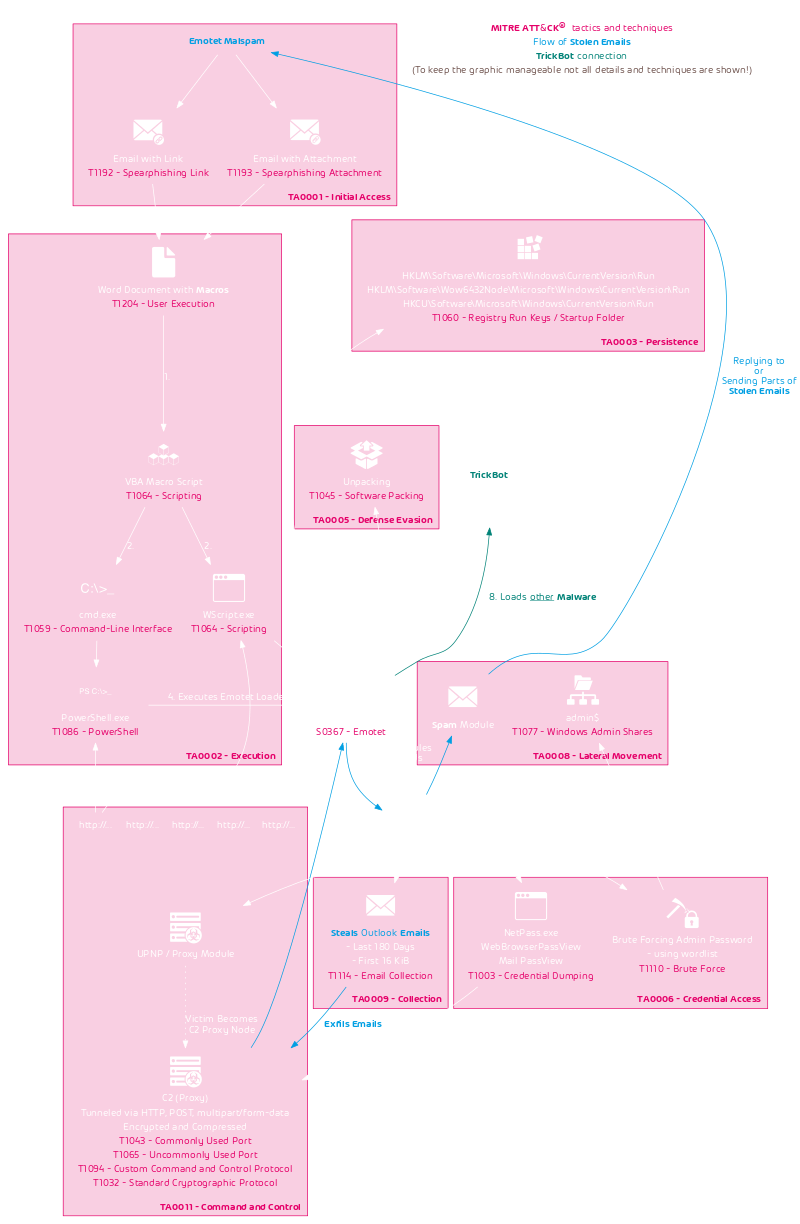

At least the initial portion of the Emotet infection chain and its used tactics and techniques as defined by the MITRE ATT&CK framework are outlined in the following flow diagram:

Of particular interest is that Emotet steals emails from victims and uses them as templates for new malspam. It uses what is known as email thread hijacking where it replies to old email threads with one of its malicious emails. Victims are much more likely to open emails from known correspondents and even more likely when that email is received in the context of an existing email conversation thread. As a result Emotet distribution campaigns have been very successful. These kind of attacks are one of the main reason why security leaders need to invest into security awareness training to mitigate IT security risks through people.

Emotet is so dangerous because in addition to its own modules to steal victims emails and misuse their computers as C2 and spam servers it delivers other malware, such as TrickBot, which ultimately leads to a Ryuk ransomware infection. So even if a victim cleans the Emotet infection they may already have additional malware running on their system(s) that are not the initial Emotet infection that they cleaned.

When victims become infected with Emotet they become part of the Emotet botnet.

Botnet

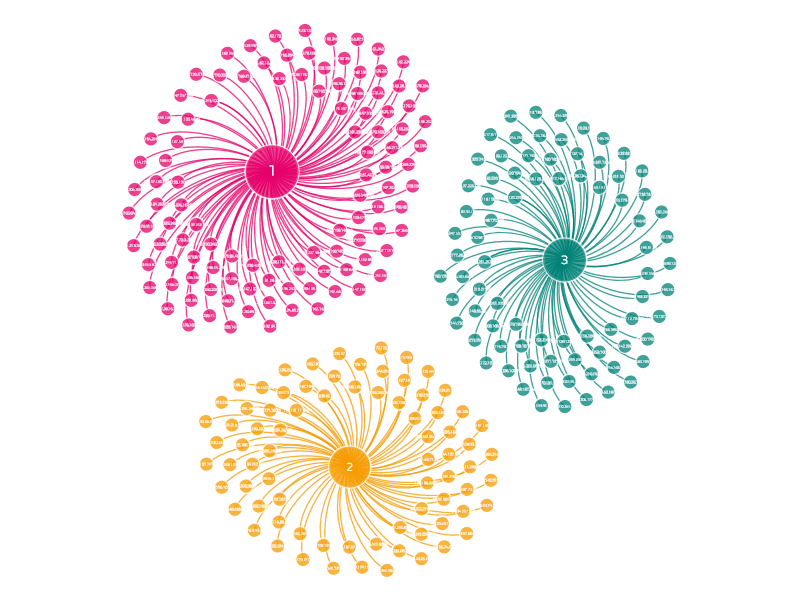

The Emotet botnet is split into separate botnets. Researchers called them Epoch 1 and 2 because they received payload updates at different times. Each Epoch has its own unique RSA key used for its C2 communication. On 2019-09-17 a portion of the Epoch 1 botnet was separated into the Epoch 3 botnet.

Each bot connects to C2 servers of its Epoch. If a victim is infected by an Emotet document belonging to Epoch 1, the document will download the Emotet loader from the Epoch 1 infrastructure and subsequently become part of Epoch 1.

The current structure of the Emotet botnet’s Tier 1 C2 servers is as follows:

Changes are deployed to the E2 botnet first. It is possible that this is done as a test to ensure that in case of introduced breaking changes only one part of the total botnet is lost.

(Recent) History

While we could dig deep into the entangled history of Emotet, its origins and shared code with Feodo, or its relations to Cridex and Dridex, we rather focus on the more recent history.

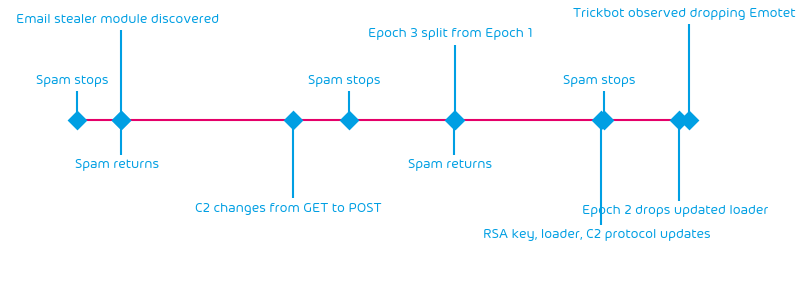

As hopefully everyone knows that currently (at the time of writing) the Emotet botnet does not send spam. The botnet often has these breaks. But it often comes back from such a break with updates rendering it more dangerously as before. A timeline of recent “spam breaks” is as follows:

Returning 2018-10-31 Emotet delivered a new Email Stealer Module. Returning 2019-09-16 Epoch 3 was split from Epoch 1. In preparation of this publication on 2020-04-29 TrickBot (a notorious malware often distributed via Emotet) has been observed dropping the Emotet loader. Speculations are that due to the long absence in Emotet malspam, which is used to seed the botnet with new bots, and current infections being constantly cleaned, the number of Emotet bots may have shrunk to a critical low number, so they are seeded by the operators behind the TickBot malware in a quid-pro-quo for Emotet’s TrickBot distribution efforts. But these are only speculations and nothing clear is known at this time.

What is known is that now with changes to the Emotet loader being dropped from Epoch 2 since 2020-04-20 the questions are when and with what new tricks will Emotet return this time. Hence, Hornetsecurity’s Security Lab has analyzed the recent changes in the Emotet malware.

Technical Analysis

Due to a lack of current Emotet spam we can not analyze any malicious emails or documents. We therefore present an analysis of the Emotet loader binary.

Emotet Loader Binary

We analyzed both the “old” version that was dropped from Epoch 1 on 2020-02-20 (which has not received any notable changes since the 2020-02-05 update), and the “new” version dropped from Epoch 2 on 2020-02-20 onwards.

Packer

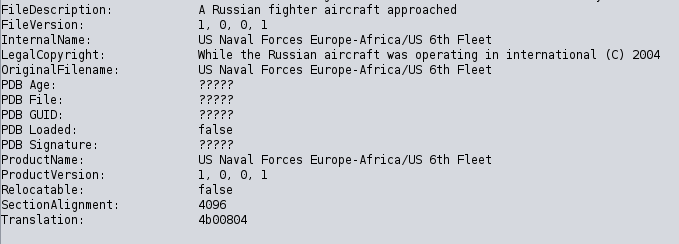

The metadata of the new version contains fragments of news article text. The File Description, Internal Name, Original Filename, Product Name, and Copyright texts are filled with fragments of news articles:

This is another indicator that Emotet uses the same packer as Trickbot, which has been seen with news article text in its metadata shortly before Emotet featured news article texts. Researchers have duped this crypter “Exes’r’rus” [JRoosen].

Because malware packers frequently change, this change is not unusual. It has been seen around 2020-02-14, but The Emotet loader payload can still be extracted via generic (and automated) unpacking mechanisms.

Obfuscation

Emotet added more obfuscation. The most notable change is control flow flattening and junk code. This makes the binary more annoying to analyze as well as allow for simpler polymorphic changes. Most of the obfuscation was already added in the 2020-02-05 change.

Control Flow Flattening

Control flow flattening is an obfuscation technique. It splits a code sequence into multiple parts and rearranges then in a way that is more difficult to follow. A common way is to place the code parts into a loop and on each loop run executing different code parts in the loop body determined by a state variable.

The code sequence:

CODE_1; CODE_2; CODE_3; return;

is turned into:

state = STATE_1

do

{

if ( state > MAGIC_VALUE_1 )

{

if ( state == STATE_2 )

{

CODE_2;

state = STATE_3;

}

if ( state == STATE_1 )

{

CODE_1;

state = STATE_2;

}

}

else if ( state == JUNK_STATE_1 )

{

JUNK_CODE_1;

state = STATE_4

}

else

{

if ( state == STATE_3 )

{

JUNK_CODE_2;

state = JUNK_STATE_1;

}

if ( state == STATE_4 )

{

CODE_3;

return;

}

}

} while(1);

While semantically identical the second code is harder to follow.

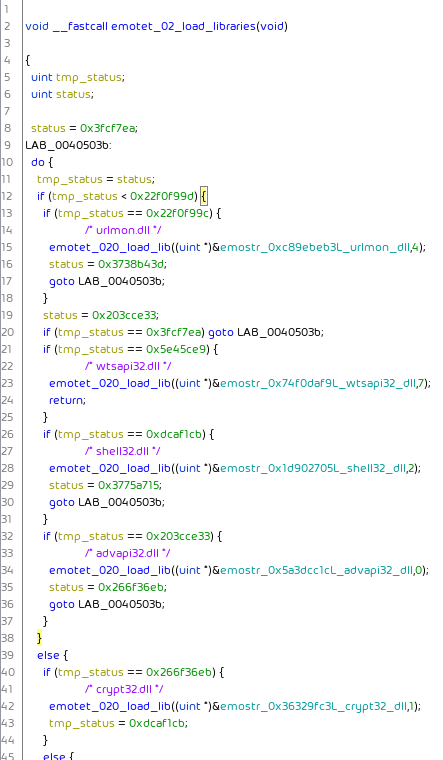

In Emotet this looks like:

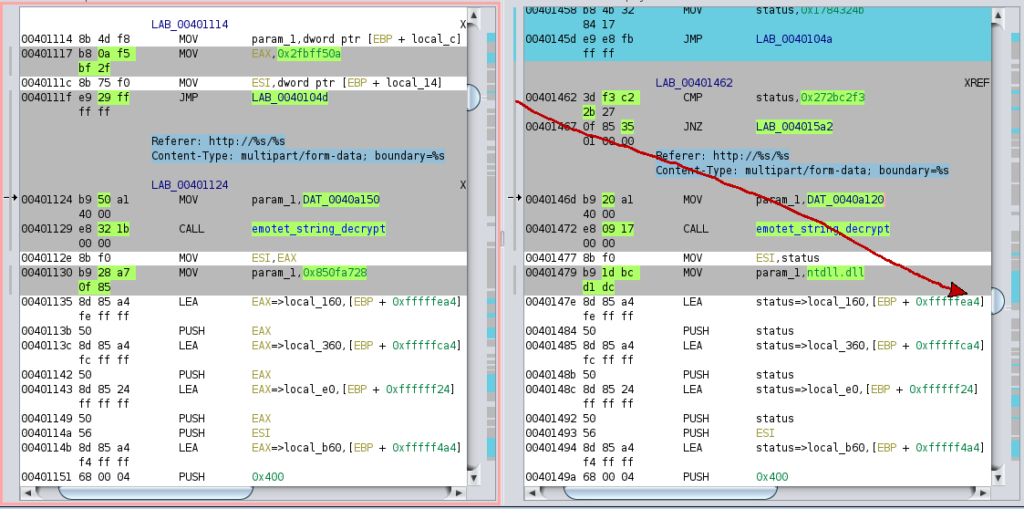

Emotet uses this to move code blocks around, as can be seen in this example, where the code block setting up the headers of the HTTP C2 communication is near the beginning of the function in one binary and near the end of the function in another binary:

Junk Code

Another technique Emotet uses is called junk code. Here useless code that does not change the semantics of a program is added.

The code sequence:

unsigned int function(unsigned int n)

{

if (n == 0)

return 1;

return n * function(n - 1);

}

is turned into:

unsigned int function(unsigned int n)

{

unsigned int a = 1234;

unsigned int b = 4321;

a = n + b;

b = n + a;

if (n == 0 && a > 10 && b > 20)

{

b = n - a;

n = b;

return 1;

}

a = b + 42;

return n * function(n - 1);

}

Here the calculations on the variables a and b are irrelevant code. They do not influence the result of the code at all. However, an analyst does not know which calculations are important and which are not. Hence, while semantically identical the second code is harder to understand.

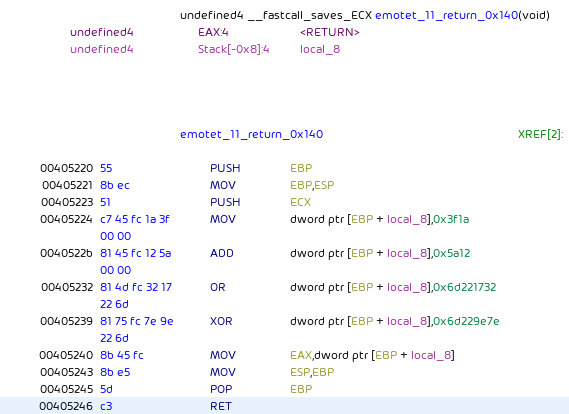

Luckily modern analysis software is able to simplify artificially complicated code. So a complex looking function:

is automatically reduced to a return of a static value:

This is used in the next obfuscation method.

Opaque Predicates

Opaque predicates are branch conditions for which the outcome is already known, but which still need to be evaluated at runtime. An example would be a code that gets the current time twice. Because time never goes backwards the first value will not be greater than the second:

time_t a = time(NULL);

time_t b = time(NULL);

if ( a <= b )

CODE;

else

JUNK_CODE;

While to a human this is logical, a machine would still need to evaluate what values a and b have to determine whether to take the jump or not.

Emotet uses functions with a static return value – see previous junk code example above – and uses their return values as a branch condition:

The branches used for control flow flattening also use opaque predicates, as the state variable changes predictable but must be evaluated at runtime.

Dynamic Library and Function Resolution

All library calls are dynamically resolved by hash. Previous versions stored the resolved functions. Now they are just-in-time resolved before every call.

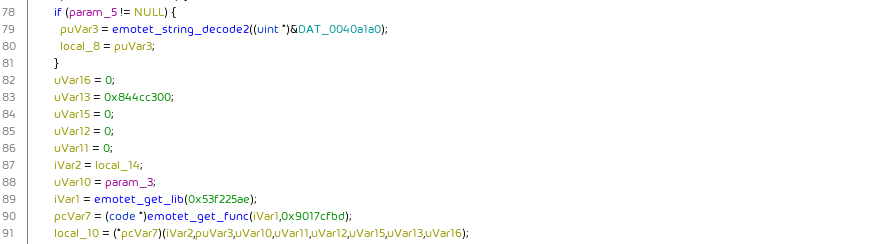

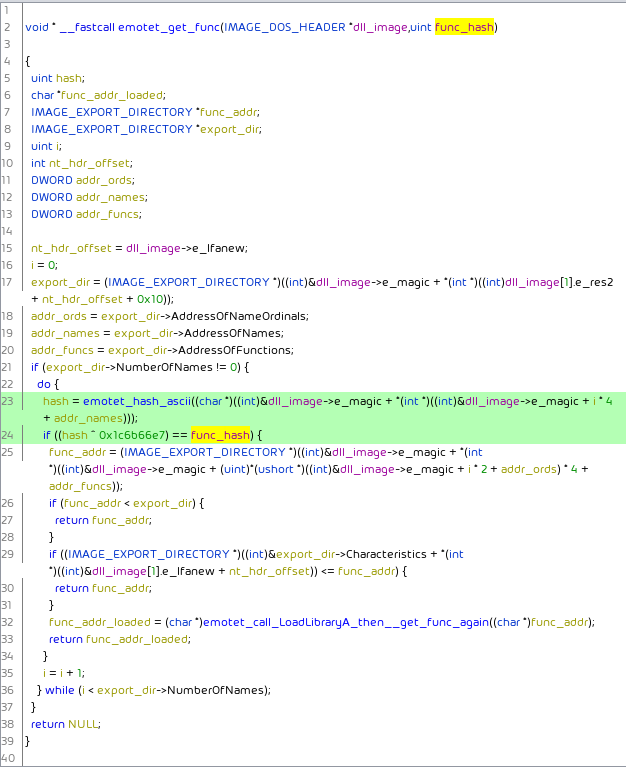

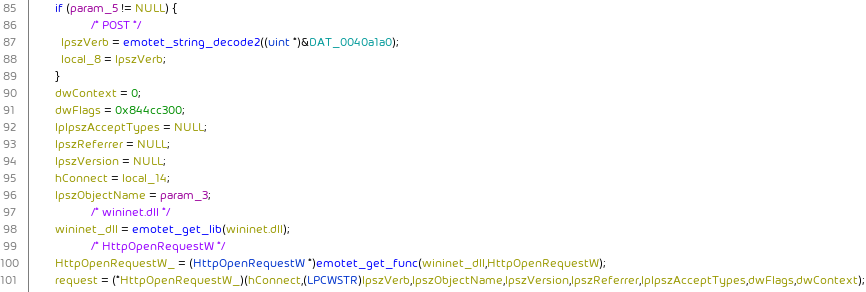

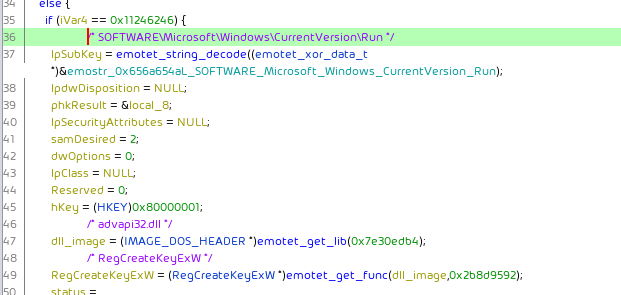

For each library call, first the library is obtained (emotet_get_lib()). Then the address of the desired function is obtained (emotet_get_func):

Libraries are resolved via the InLoadOrderModuleList reachable from the Process Environment Block (PEB) (FS:[0x30]):

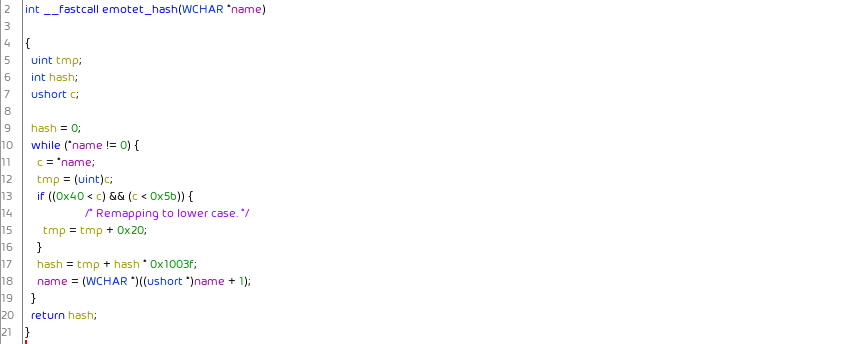

Then the DllBaseName for every loaded module is hashed and compared against the current queried hash. If the hash matches the DllBase is returned. The GET_LIB_XOR_VALUE varies for each binary. This means that library hashes change from sample to sample and can not be pre-calculated. They must be calculated for each sample individually.

Addresses of functions are obtained via manually traversal of in this case the export directory data structure. Each exported function name of the previously resolved DLL’s image is iterated over and hashed. If the hash matches the function’s address is returned:

Emotet still uses the same hashing algorithm as previous versions:

The emotet_get_func() function uses a variation without mapping the uppercase characters to lowercase, i.e., its hash is case-sensitive, and ingesting a char string instead of a wchar string. The emotet_hash() function is also heavily laced with junk code, which luckily the decompiler already simplified and/or discarded.

Using the Ghidra analysis scripts emotet_lib_imports.py and emotet_func_imports.py the called library and function names can be reconstructed from their hashes:

The following libraries that are usually not loaded into a process by default are loaded via LoadLibraryW:

shell32.dll userenv.dll urlmon.dll wininet.dll wtsapi32.dll advapi32.dll crypt32.dll shlwapi.dll

Handles to the libraries are stored to allocated memory. But never used. We have found other functions and code paths that are never used. These is likely leftover code that was not removed during code updates.

XOR Obfuscation

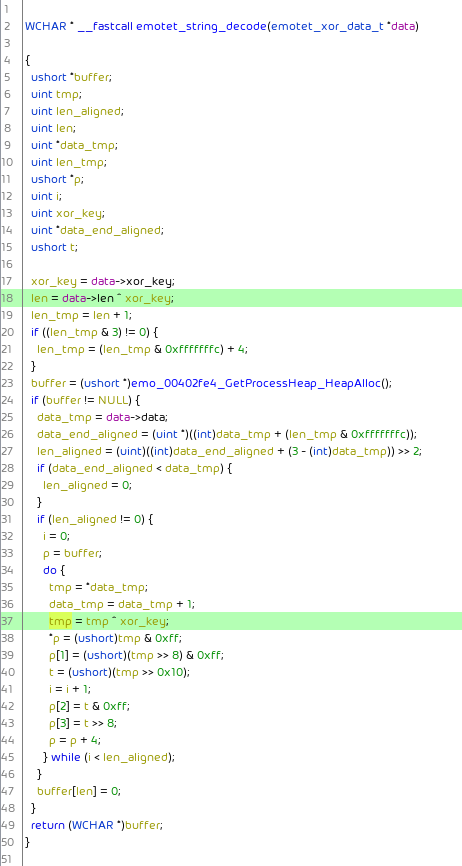

Strings and the RSA key are (as in previous versions) XOR obfuscated. The use the following structure:

typedef emotet_xor_data_t {

uint32_t xor_key;

uint32_t len;

uint32_t data[];

} emotet_xor_data_t;

They are decrypted by first XOR’ing len with xor_key. Then XOR’ing decoded and to 4-byte boundaries aligned len bytes of data with xor_key:

The XOR key again changes from binary to binary. But still the decoding process can be automated, e.g. the emotet_string_decode.py script can decode used strings:

They are also just-in-time decrypted on demand to a new memory allocation. The memory allocation holding the decrypted string is deleted again after use for every use of the string.

Static Analysis Tutorial

With the basics of the new obfuscation techniques covered we quickly outline how Emotet can still be analyzed.

- Unpack your Emotet sample. E.g., using the free open source community developed CAPE sandbox [CAPE].

- Import into Ghidra [GHIDRA].

- Run Auto Analysis.

- Run

emotet_lib_imports.pywithcurrentAddressin 2nd function called inentryfunction (this is what we refer to as theemotet_get_libfunction). - Run

emotet_func_imports.py(selectingfunc_names.txt) withcurrentAddressin 3rd function called inentryfunction (this is what we refer to as theemotet_get_funcfunction). - Run

emotet_string_decode.pywithcurrentAddressinemo_*_LoadLibraryWfunction. - Run

emotet_string_decode.pywithcurrentAddressin 1st function called inemo_*_LoadLibraryWfunction.

Then you have:

- Comments for library and function resolution.

- Two enum types

emotet_{lib,func}_hashwith enums for the library and function hashes, which you can optionally apply to theemotet_get_{lib,func}functions. - Emotet strings decrypted and set as comments, labels as well as searchable bookmarks.

C2 communication is found by searching for usage of the HttpSendRequestW function. The type of request and request headers can be found by backtracking via the first parameter (hRequest) to HttpSendRequestW. Alternatively usage of the HttpOpenRequestW function, the InternetConnect function, the POST string, or the Referer: http://%s/%s ... string will yield the relevant code.

C2 IP storage can be found by searching for the %u.%u.%u.%u string. These octets are filled from data in a allocation we named emotet_c2_data. This allocation is filled from a data location we named emotet_c2_list. If you run emotet_ip_decode.py with currentAddress set to the address of emotet_c2_list the C2 list is decoded and annotated as a comment.

The C2 HTTP request template looks like:

POST Referer: http://%s/%s Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=%s --%S Content-Disposition: form-data; name="%s"; filename="%s" Content-Type: application/octet-stream

RSA key is found by searching the source of the 3rd parameter (pbEncoded) to the CryptDecodeObjectEx function. It is XOR encoded like the strings. You can run emotet_data_decode.py with currentAddress on the data location passed to the function that returns the pointer that is then passed as the 3rd parameter to the CryptDecodeObjectEx function. You can use openssl asn1parse -inform DER -in emotet_key.bin to check if the decoded emotet_key_bin is valid. The key must be the exact length without any appended bytes beyond the ASN1 DER sequence stream.

Search for functions using the OpenSCManagerW function. One function will contain an assignment to a data location. Emotet uses OpenSCManagerW to check whether it has admin rights or not. This is where what we call the is_admin flag is set. Use “Auto Create Structure” on the data reference and name it emotet_data and name the field assigned the value 1 is_admin.

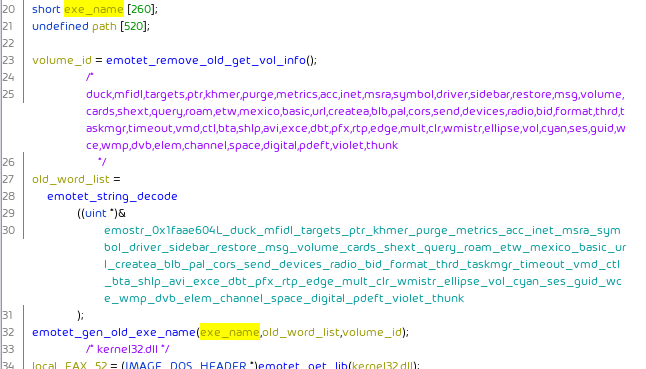

Search for functions using the string %s\%s.exe. This is where the executable path is constructed. In its vicinity the emotet_data data location is accessed. Determine by their usage as parameters to the _snwprintf function which of the two fields in the emotet_data structure is the exe_path and which is the exe_name.

Then use “References -> Find use of emotet_data_t.exe_name” to find out how the exe_name is generated. Do the same for the exe_path. The exe_name will also be used to generate the service name. Relevant code is found by searching for CreateServiceW.

Persistence via run keys is found via RegCreateKeyExW and/or the SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run string.

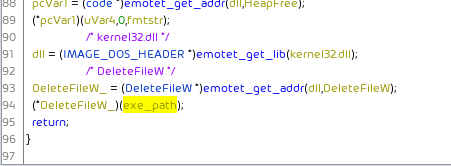

Searching for usage of the %s:Zone.Identifier string finds where Emotet deletes its Zone.Identifier ADS, which on Windows is used to mark files downloaded from external sites as potentially unsafe.

As an interesting side note older new versions contained code removing old Emotet binaries which names were generated from word lists:

This functionality has been removed from the latest version, indicating that the migration to the new version has been completed for Epoch 2 and there is no need to delete old binaries anymore:

(Either that or the function has moved and has not been picked up by our string deobfuscator script.)

The following video demonstrates how our scripts can be used to jump start your own analysis of the Emotet loader:

Download our scripts on Github.

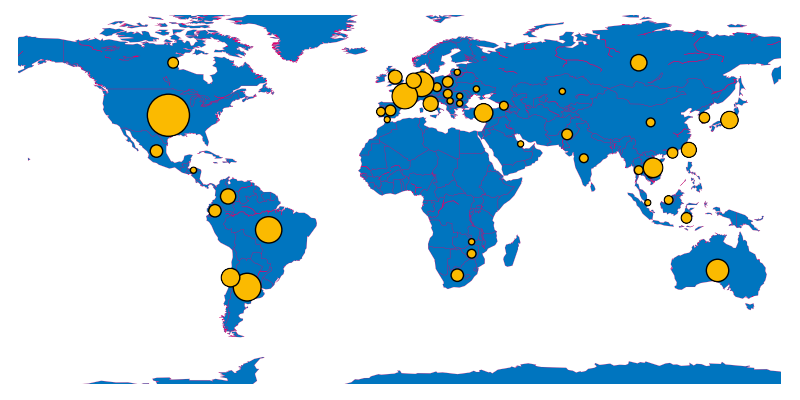

Tier 1 C2 geolocation

Emotet’s tier 1 C2 proxies and servers are geolocated all over the world:

(C2 IP list as observed 2020-04-20.)

Conclusion and Remediation

To protect against Emotet the US CERT recommends to “implement filters at the email gateway to filter out emails with known malspam indicators” [USCERT].

Hornetsecurity’s Spam and Malware Protection with the highest detection rates on the market are not impacted by the updates to the Emotet loader (as the loader is never send directly via emails) and thus will (as in the past) block all Emotet malspam indicators, such as macro documents used for infection, but also known Emotet download URLs. Hornetsecurity’s Advanced Threat Protection extends this protection by also detecting yet unknown malicious links by dynamically downloaded and executing the potentially malicious content in a monitored and sandboxed environment. Meaning that even in the event the Emotet loader changes is accompanied in a change in delivery tactics, Hornetsecurity is prepared.

Beyond blocking the incoming Emotet emails defenders can use public available information by the Cryptolaemus team, a voluntary group of IT security people banding together to fight Emotet. They provide new information daily via their website [CryptolaemusWeb]. There you can obtain the latest C2 IP list for finding and/or blocking C2 traffic. For real-time updates you can follow their Twitter account [CryptolaemusTwitter].

We acknowledge that our presented analysis only scratches the surface of the Emotet malware complex, but when Emotet returns so will we, with updated analyses of new malicious documents and/or any other new developments.

References

- [USCERT] https://www.us-cert.gov/ncas/alerts/TA18-201A

- [JRoosen] https://twitter.com/JRoosen/status/1228215329022603267

- [CERTPL] https://www.cert.pl/en/news/single/whats-up-emotet/

- [CAPE] https://capesandbox.com/

- [GHIDRA] https://ghidra-sre.org/

- [Cryptolaemus] https://paste.cryptolaemus.com/

- [CryptolaemusTwitter] https://twitter.com/Cryptolaemus1

Samples Used

Hashes

| SHA256 | Description |

cc96711da9ef7b63d5f1749d8866b0149f84506f9d53d79de018dac92e9443a0 |

Epoch 1 sample (“old” version) 2020-04-20 |

4c3acc885006faebe59e0bfdd452499056d8fcc9e6a810d7ff93762ce1a061ad |

Epoch 1 sample unpacked payload 2020-04-20 |

4250a3ab9044b4a3a5f8319e712306bb06df61b1dee8b608505c026bacba4aa1 |

Epoch 2 sample (“new” version) 2020-04-20 |

14f8463a86bbae338925fbbcb709953ae7f1bffdb065fee540b6fa88fbbce70e |

Epoch 2 sample unpacked payload 2020-04-20 |